The through-line in Luminate Intelligence’s Key Changes in the Music Industry special report is a need for change. In the face of a revenue slowdown across both recorded and live music, the industry’s main players want to build new income streams and add more value to their creations.

The reality, though, is the majority of these initiatives will do little to nothing to impact everyday working musicians and indie artists without major label backing. And while recent legislation in both the U.S. and UK aims to help musicians directly, these efforts will prove not enough if the root causes for why musicians are struggling in the first place are left unaddressed.

Amid the far-reaching cost-cutting measures proposed in President Trump’s deeply unpopular “Big Beautiful Bill” in early July was, surprisingly, a bipartisan assist for indie musicians. The HITS Act was originally introduced in 2020 as the pandemic forced countless musicians to cancel shows and stay home, losing out on vital income, but it finally made it through by hitchhiking on the spending bill.

The legislation will create a new tax code that allows musicians to expense up to $150K of production-related costs in the year they were incurred instead of over several years, a benefit already afforded to the TV, film and theater industries.

Across the pond, the UK government unveiled a “label-led” initiative to support music artists, spearheaded by three core principles outlined by trade group BPI with backing from the Association of Indie Music: forgiven unrecouped advances for legacy artists, per diems for songwriters attending label-backed sessions and camps and a pay increase for session musicians.

The UK divisions at the “Big Three” labels — Universal Music Group, Sony Music and Warner Music Group — have all committed to the new precepts (each already had an unrecouped forgiveness program in place), and BPI encouraged its 500-plus indie label members to hit similar targets based on their available resources.

These moves are certainly well intentioned, but in their current form, they may not be enough to make a meaningful difference for musicians. Critics of the UK initiatives said as much following the announcement; even the region’s Musicians’ Union, which approved the session musician pay raises, said it is “disappointed that the labels have not addressed the key issues with music streaming economics.”

In fact, paltry royalties from streaming are easily the biggest issue for working musicians. Modernized tax codes and higher day rates are obviously welcome, but they don’t make up for the fact that most artists and songwriters, even when they own both their master recordings and publishing, make fractions of pennies from streams.

Take Spotify, easily one of the most used music DSPs in the world. The company’s payment calculations aren’t publicly known, but indie catalog investment firm Duetti estimated artists earned about $3.50 per 1,000 streams in 2024 –– although it’s worth noting that music DSPs don’t technically pay on a per-stream basis but rather on several factors including subscriptions and ad revenue splits.

And while streaming undoubtedly allows more artists than ever to reach fans without the need for a label, a song on Spotify needs at least 1,000 streams within 12 months to get paid at all as of last year — a policy that ultimately favors artists with major label backing. Spotify is also potentially paying artists even less this year thanks to the legal “bundle” loophole that resulted in lower payouts for songwriters and music publishers.

Spotify called Duetti’s findings “ridiculous” and noted in its annual Loud & Clear report that it paid out over $10 billion to the music industry in 2024, though Music Business Worldwide estimated based on the report that less than 0.6% of artists on Spotify earned $10,000 or more in royalties.

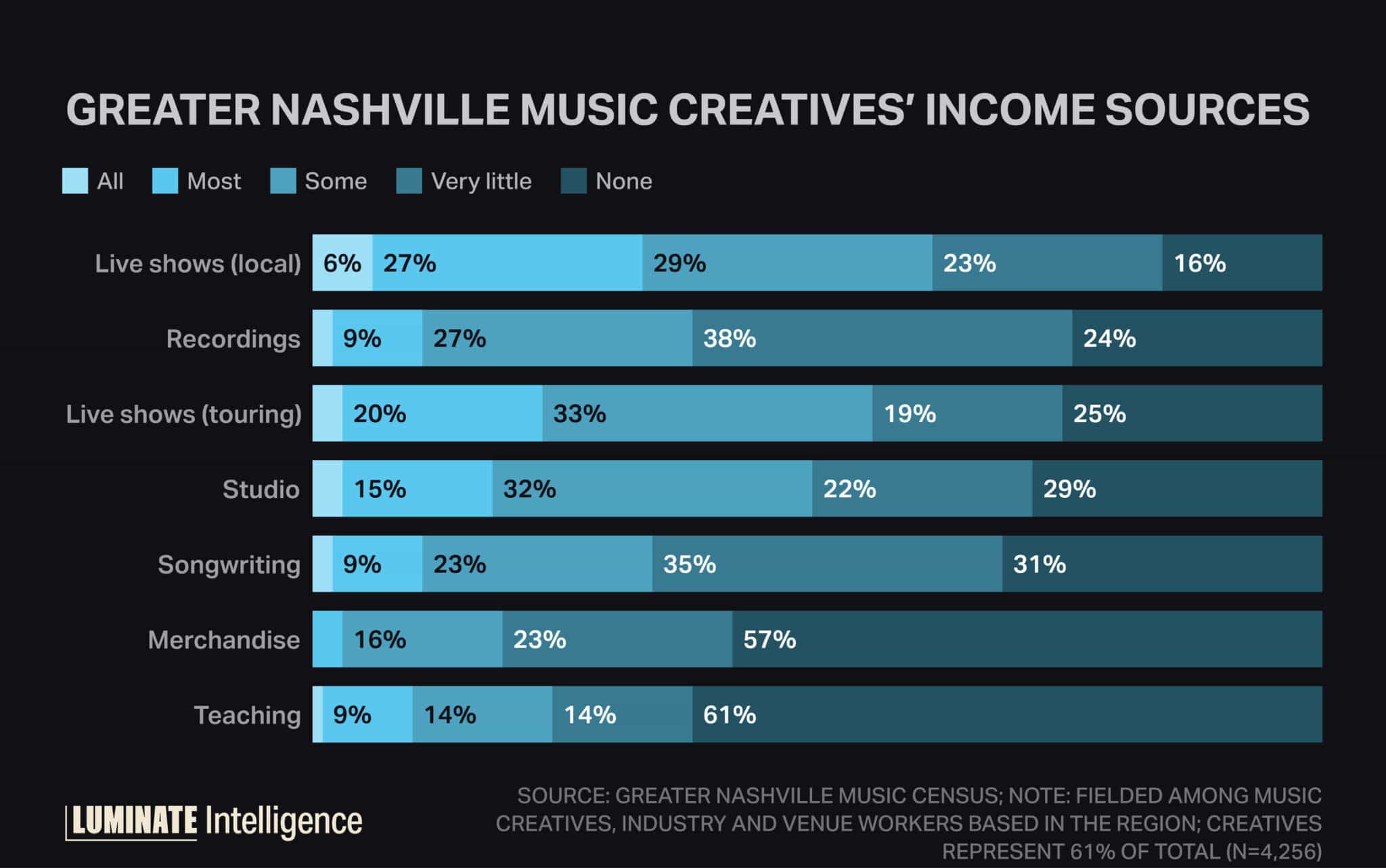

There isn’t much data on the cost of living for musicians in the whole U.S. (an issue in itself), but the Greater Nashville Music Census of 2024 at least offers a case study for musicians living in one of the most music-centric U.S. cities. Those surveyed made an average of $54K annually from music, but 62% said little to none of their income is from music recordings.

Even the simple idea of coming home from touring with a profit is becoming less attainable: A 2024 Pirate Studios survey found 72% of artists have had no profit from touring, while 29% also saw decreased gig fees on recent tours even as expenses grew and despite rising ticket prices across the industry.

And of course, there’s the rise of AI music and the substantial impact it will have on songwriters and musicians. Some companies have agreed to specific regulations, but generative AI music platforms widely have and continue to use copyrighted material to train their models without proper compensation for the rights holders.

In fairness, there have been some positive developments in both the U.S. and the UK. Congress threw out a controversial AI-friendly provision from the spending bill, and the House of Lords has repeatedly rejected the UK government’s proposal to offer copyright exemptions for AI training. Still, these efforts are coming as AI has already made an irreversible impact on musicians. Ultimately, real change for artists needs to come from the industry itself alongside external regulations.